We have a question for you

“How does New Zealand law address the collection, use and sharing of personal information?” For many people, the immediate answer is that the Privacy Act does this. This is understandable because:

- the Act is central to the protection of privacy in this country; and

- in many scenarios, for example the handling of personal information by private sector businesses, the Privacy Act will usually be the main law, if not the only law, governing the handling of personal information.

However, our statute books are filled with all manner of specific laws that affect the collection, use and sharing of personal information in particular contexts. The Privacy Act may be the primary volume – the first book to read and understand – but often it’s not the only one. In many contexts, to understand the law that applies we need to be familiar with two or more statutes. To understand the law that applies across an entire sector, we may need to be familiar with many statutes. And to understand all New Zealand law that applies to the collection, use and sharing of personal information, we need to be familiar with a large number of laws. These other laws can make inroads into the Privacy Act. It is common for such laws to override the Privacy Act in certain respects.

The need to understand more than the Privacy Act is particularly acute if you’re working in, or interacting with, certain kinds of government agencies. In these contexts, there are often significant numbers of specific statutory provisions in other legislation that affect the handling of personal information. Frequently they contain powers relating to the collection, use or sharing of personal information that qualify or override the Privacy Act. Usually those powers enable something that the Privacy Act would not or might not allow. Sometimes, they limit what can be done with personal information.

In the remainder of this article, we’ll:

- introduce the Privacy Act;

- explain why it’s an important law but not necessarily the only law we need to think about;

- describe the way in which other laws can override or modify the Privacy Act’s application;

- explain how agency policies and protocols can fit within the legislative framework; and

- sketch out a hierarchy of laws, policies and protocols to help you see how it all slots together.

Privacy Act is important but not necessarily the only relevant law

The Privacy Act is legislation of general application that regulates agencies’ collection, storage, use, disclosure and retention of personal information. It applies to public and private sector agencies alike. In this context, “agency” doesn’t mean government agency. It’s just the word the Privacy Act uses to describe the persons and organisations to which it applies, namely, “any person or body of persons, whether corporate or unincorporate, and whether in the public sector or the private sector” (there are some exceptions, but we don’t need to worry about them here).

The Privacy Act is legislation of general application that regulates agencies’ collection, storage, use, disclosure and retention of personal information. It applies to public and private sector agencies alike. In this context, “agency” doesn’t mean government agency. It’s just the word the Privacy Act uses to describe the persons and organisations to which it applies, namely, “any person or body of persons, whether corporate or unincorporate, and whether in the public sector or the private sector” (there are some exceptions, but we don’t need to worry about them here).

So, all “agencies” as just described that handle personal information need to be familiar with the Act, particularly its information privacy principles (IPPs). Very briefly:

- IPPs 1-4 govern the collection of personal information, including the purposes for which it may be collected, where it may be collected from and how it is collected.

- IPP 5 addresses storage and security of personal information. It is designed to protect personal information from unauthorised use or disclosure.

- IPP 6 gives individuals the right to access information about themselves.

- IPP 7 gives individuals the right to request correction of information about themselves.

- IPPs 8-11 place restrictions on how agencies can use, retain and disclose personal information. These include taking reasonable steps to ensure information is accurate and up-to-date, and that it isn’t improperly disclosed.

- IPP 12 regulates the disclosure of personal information outside New Zealand.

- IPP 13 governs how “unique identifiers” (such as IRD numbers, bank client numbers, driver’s licence and passport numbers) can be used.

The Privacy Act’s IPPs can, however, be modified or overridden by:

- other Acts of Parliament;

- legislative instruments, whether under the Privacy Act (such as an Authorised Information Sharing Agreement under Part 9A of the Act) or other legislation; and

- Codes of Practice under the Privacy Act (such as the Health Information Privacy Code).

In many contexts, such as the social sector, immigration, customs, biosecurity, and the tax system, there is an array of other legislation and legislative instruments that override or modify the application of the IPPs in specific ways. And in some areas, Codes of Practice under the Privacy Act do likewise, such as the Health Information Privacy Code that modifies the IPPs for health information.

Sometimes agencies may be given specific statutory power but not the duty to collect or share personal information. In other cases the law will positively require the collection or sharing of personal information. In yet other cases, the law may prohibit the use or sharing of personal information that the Privacy Act would otherwise allow.

Agencies may need to consider multiple sources of law

This means that, depending on the context, an agency that wishes to do something with personal information may need to consider whether there are any other Acts of Parliament, any legislative instruments and/or any Codes of Practice that override or modify the application of the IPPs. This can affect some agencies more than others, depending on the agencies involved and the kinds of personal information involved. To give just a few of the many examples:

This means that, depending on the context, an agency that wishes to do something with personal information may need to consider whether there are any other Acts of Parliament, any legislative instruments and/or any Codes of Practice that override or modify the application of the IPPs. This can affect some agencies more than others, depending on the agencies involved and the kinds of personal information involved. To give just a few of the many examples:

- the Ministry of Social Development has a range of specific information gathering powers in the Social Security Act 2018;

- the Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment has a range of such powers in the Immigration Act 2009;

- the New Zealand Customs Service has wide-ranging powers in the Customs and Excise Act 2018;

- the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989 contains provisions enabling and in some cases requiring information to be provided to Oranga Tamariki or the Police in relation to the ill-treatment or neglect of children and to determine whether a child or young person is in need of care and protection;

- the Family Violence Act 2018 introduced new information sharing provisions to contribute to addressing family violence;

- the Health Act 1956 enables the disclosure of health information in a range of situations; and

- Inland Revenue has a range of powers in the Tax Administration Act 1994.

When other legislation or a Code of Practice under the Privacy Act does apply, referring only to the Privacy Act’s IPPs may result in legal error. An agency may decide not to do something, thinking that it can’t, when in fact another and prevailing source of authority allows it to. Similarly, an agency may decide to do something with personal information, thinking it can under the Privacy Act, when other legislation does not allow it. Or legislation may positively require the sharing of personal information for specified purposes.

The manner in which laws override or modify the Privacy Act

When other legislation or a Code of Practice under the Privacy Act overrides or modifies the Privacy Act, usually it will only do so partially. For instance, it may modify certain IPPs yet leave other parts of the Act to apply. For example, the Statistics Act 1975 empowers Stats NZ to collect information for statistical purposes yet other IPPs still apply in certain contexts. At the same time, the Statistics Act imposes substantial constraints on the disclosure of information that identifies individuals and those constraints prevail over the Privacy Act’s IPP 11 (Disclosure of personal information). Similarly, a Code of Practice under section 46 of the Privacy Act or an Approved Information Sharing Agreement under Part 9A of that Act may modify the application of some IPPs but not others.

Agency policies and protocols that may apply to an agency’s treatment of personal information

An agency may develop policies or protocols that address how the agency will treat personal information in certain contexts. Agencies are free to do this as long as the policies and protocols are not contrary to obligations on them under applicable laws and Codes of Practice. For example, Stats NZ has a range of policies and protocols, including an Information privacy, security, and confidentiality policy, Data integration guidelines and Privacy and confidentiality guidelines.

Hierarchy of laws, policies and protocols and rules of precedence

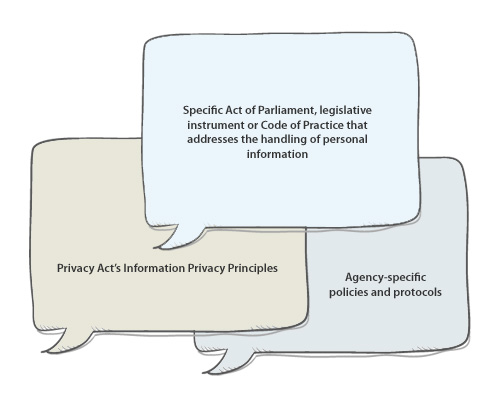

The potential existence of:

- additional legislation, legislative instruments and Codes of Practice; and/or

- agency-specific policies and protocols,

relating to an agency’s handling of personal information may mean an agency needs to be aware of multiple sources of applicable law and policy.

Where specific legislation overrides the Privacy Act in some but not all respects and the agency concerned has implemented policies or protocols as to how it will handle personal information, the hierarchy of governing law and policy is as set out in the diagram below and can be expressed as rules of precedence.

The rules of precedence are these:

The rules of precedence are these:

1. The specific Act of Parliament, legislative instrument or Code of Practice prevails over affected IPPs in the Privacy Act as well as over anything in agency-specific policies and protocols that is inconsistent with the Act, instrument or Code. This ‘prevailing’ might, depending on the Act, instrument or Code, allow something an IPP would not allow or constrain something an IPP would allow.

2. Those of the Privacy Act’s IPPs that are unaffected by the Act, instrument or code are left intact and continue to apply. Sometimes an IPP will only be affected in part. To the extent it is not affected, it might be left to apply.

3. Similarly, agency-specific policies and protocols are left intact and continue to apply to the extent that they are not inconsistent with the Act, instrument or Code and not contrary to the IPPs that are left intact. Note that a policy may constrain something an IPP would allow but cannot allow something an IPP constrains.

These rules of precedence explain why, in the diagram, the top speech bubble is complete and overrides relevant parts of both of the other speech bubbles and why the left speech bubble overrides relevant parts of the right one.

Would you like a PDF of this article?